Sentence Fragments and Run-ons in SAT Writing: Tips and Questions

Author

Hartwell

Date Published

Can you recognize a sentence when you see one?

Most people will automatically answer that they can. But correct sentence structure is one of the most commonly-tested grammatical concepts on the SAT Writing section.

What does it take to make a sentence complete? How can you recognize a fragment or a run-on? Read on to figure out how the SAT manages to trick so many students with this seemingly easy concept.

In this guide I am going to show you:

What constitutes a complete sentence

How prepositional phrases, appositives and non-essential clauses can make sentences more difficult to understand

How to recognize and fix fragments

How to recognize and fix run-on sentences

Strategies to attack these kinds of questions

Examples of this kind of question from the SAT

Test Yourself

To start, take a look at the following. Some of these are correct sentences. Others are fragments or run-ons. Can you tell which are which? Do you understand why the incorrect sentences are incorrect?

-1600x622.jpg)

Answers: 1. Sentence; 2. Fragment; 3. Run-on; 4. Sentence; 5. Fragment; 6. Fragment; 7. Sentence; 8. Fragment; 9. Run-on

How did you fare? As you can see, accurately identifying a sentence every time can be more challenging than one might expect, and understanding the reasons for an incorrect sentence's flaws is even more so. Continue reading, and we will thoroughly explain what is required for a sentence to be correct.

What Is a Sentence?

Sentences may be short or long, and they can be simple or complex. To form a correct and complete sentence, you really only need two basic parts: a subject and a verb that agrees with that subject.

When a subject and a properly conjugated verb appear together—along with any additional words connected to them—they create what is called an independent clause. Don’t worry, you don’t need to memorize that term for the SAT! Still, it’s a helpful idea to understand as we continue learning about sentences.

An independent clause works as a complete sentence on its own because it expresses a full thought and makes sense by itself.

For example, here are some independent clauses:

The girl runs.

The girl with bows in her hair runs.

The young girl with bows in her hair runs through the village square.

Each of these sentences contains a subject, a correctly conjugated verb, and makes sense on its own without needing more information. In these examples, the subject is “girl” and the verb is “runs,” which is properly conjugated in the third person singular to match the subject. Even if you removed the extra words from the second and third sentences, they would still be complete and meaningful.

There is, however, one situation where you can have a complete sentence without being able to clearly identify the subject and verb: when giving commands. In commands, the subject is always the understood “you”, so it does not need to be written.

Examples:

Run!Speak!Run down the street and speak to your grandmother!

Fortunately, this idea doesn’t appear very often on the SAT, but it’s still important to understand in case it does.

So now you know the basics of what makes a simple sentence! But sentences can include more than just one independent clause, and this is where things begin to get more complex. A sentence may contain a second independent clause, or it may connect an independent clause to a dependent clause.

Sentences with More than One Independent Clause

Sometimes, a sentence may contain more than one independent clause. When this happens, it’s important to make sure they are connected correctly. If they are not, the result is a run-on sentence. We’ll go into more detail about run-ons later, but first let’s look at the correct ways to link clauses together.

There are several methods for combining two independent clauses into a single compound sentence:

Method 1: Don’t join them at all.

This is often the simplest solution. You don’t have to connect the clauses—just separate them with a period.

Example:

Julia and Louise both like to eat pizza. They both love pepperoni.

Method 2: Join the clauses with a comma and a coordinating conjunction.

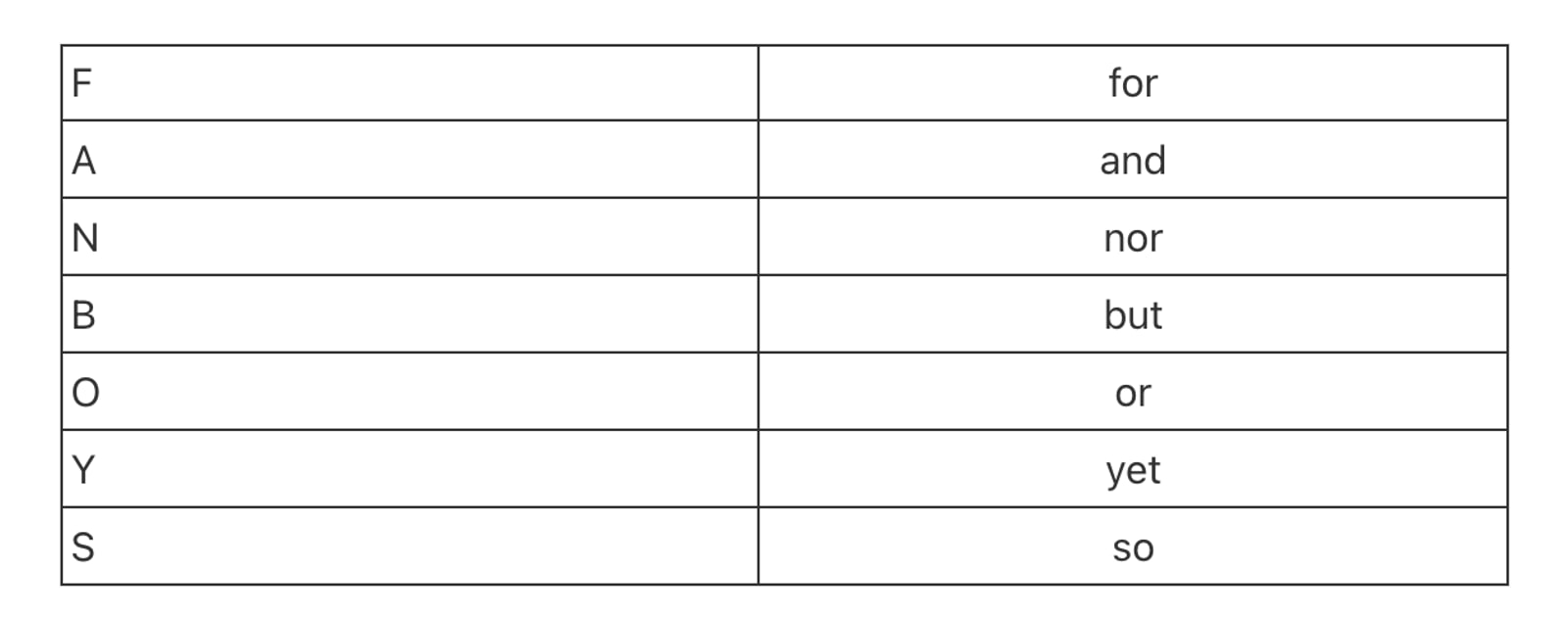

Coordinating conjunctions can be remembered with the acronym FANBOYS:

Example:

Julia and Louise both like to eat pizza, for they both love pepperoni.

Method 3: Join the clauses with a semicolon.

A semicolon works almost the same way as a period. You can connect two independent clauses with just a semicolon.

Example:

Julia and Louise both like to eat pizza; they both love pepperoni.

Method 4: Join the clauses with a semicolon and a conjunctive adverb.

A semicolon can be followed by a special connecting word called a conjunctive adverb. Some of the most common ones are: however, nevertheless, therefore, moreover, consequently.

Different conjunctive adverbs show different relationships:

however / nevertheless → show a contrast

therefore / consequently → show cause and effect

moreover → adds or expands the information

Example:

Julia and Louise both like to eat pizza; moreover, they both love pepperoni.

Important rule: Conjunctive adverbs can be used after either a semicolon or a period, but they must always be followed by a comma.

Method 5: Turn one of the independent clauses into a dependent clause.

Another option is to make one clause dependent (also called subordinate). We’ll study dependent clauses in more detail soon, but here’s a basic example:

Example:

Since they love pepperoni, both Julia and Louise like to eat pizza.

Understanding how dependent clauses function is essential for recognizing and avoiding run‑ons and fragments. So, let’s now take a closer look at how dependent clauses can be used.

Sentences with Dependent (or Subordinate) Clauses

The terminology here is less important than the idea. Like an independent clause, a dependent clause contains both a subject and a verb. However, unlike an independent clause, it cannot stand on its own as a complete thought. In other words, if you read a dependent clause by itself, it feels incomplete.

Most often, dependent clauses are used to describe the circumstances in which the action of an independent clause takes place.

Example:

While she was gardening, Jenny found an old penny.

Here, the dependent clause “While she was gardening” provides context for when Jenny found the penny. Notice that “While she was gardening” by itself doesn’t form a complete thought—it only sets the scene for more information to follow.

Be Careful! Everyday speech often uses dependent clauses as if they were complete sentences.

Take this short dialogue as an example:

You: “Look at this cool old penny I found! It’s from 1933!”

Friend: “Wow, that’s cool. Where did you find it?”

You: “While I was gardening.”

In spoken English, this sounds perfectly natural, because your listener can connect it to what was said before. But in formal written English, “While I was gardening” is not a complete sentence. It’s only a dependent clause referring back to the independent one: “I found a penny.”

On the SAT (and in academic writing in general), a sentence that consists only of a dependent clause is always considered incorrect.

We’ll explore this idea in greater detail in the upcoming Fragments section.

Sentences with Prepositional Phrases, Appositives, and Relative Clauses

Some sentences include extra phrases or clauses that provide more detail about a noun or a verb. These additions give variety and richness to writing. However, it’s very important to remember: none of these can replace an independent clause. A sentence still needs a subject and a verb that form a complete thought.

Prepositional Phrases

A prepositional phrase begins with a preposition (such as in, on, under, by, with, about, etc.) and usually ends with a noun. Prepositional phrases give additional detail about something in the sentence.

You can place a prepositional phrase in different positions, depending on what it modifies:

The man in my kitchen was making sandwiches.

The man was making sandwiches in my kitchen.

Key points to remember:

If you remove the prepositional phrase, the sentence should still be complete:

The man was making sandwiches.

A prepositional phrase cannot stand alone as a sentence:

In my kitchen.

Relative Clauses

A relative clause gives extra information about a noun. It usually comes after the noun, sometimes even between the subject and the verb.

Relative clauses are introduced by relative pronouns such as: who, that, which, whose, where.

Examples:

The man, who was standing in my kitchen, was making sandwiches.

The man, whose sandwiches we enjoyed, works in the café down the street.

Removing the relative clause still leaves a complete sentence:

The man was making sandwiches.

The man works in the cafe down the street.

Appositives

An appositive is a noun (or noun phrase) placed directly next to another noun to rename it or add more description. Appositives are usually set off by commas. Appositives can be a single word, or a longer phrase.

Examples:

My dad, Phil, works in the café down the street.

My father, the man who is in the kitchen, likes making sandwiches.

Sandwiches, one of my favorite foods, are delicious.

Just like relative clauses and prepositional phrases, appositives can be removed, and the sentence will still make sense:

My dad works in the café down the street.

My father likes making sandwiches.

Sandwiches are delicious.

Now you have seen several ways to add detail to complete sentences—using prepositional phrases, relative clauses, and appositives. Next, let’s turn to what can go wrong: the common mistakes that lead to incomplete sentences.

What Is a Fragment?

A fragment is an incomplete sentence. It may look like a sentence, but it’s missing something essential—usually a subject, a verb, or a complete thought.

There are six major errors that can cause a sentence to turn into a fragment:

No verb

A verb ending in ‑ing (or a past participle in ‑ed) without a helping verb

No subject

A sentence beginning with a subordinating conjunction but missing a main clause

A detail or phrase incorrectly separated from its main clause

A nonessential clause or prepositional phrase without a complete sentence

Let’s examine each mistake one by one.

Fragments Without a Verb

How to recognize: Ask yourself “What is the subject doing?” If you can’t answer that, the sentence is missing a verb.

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

John, after winning the trophy. (What did John do?)

Ten cakes and two dozen cupcakes. (What happened to them?)

Next Tuesday. (What is next Tuesday?)

Corrected Versions:

John, after winning the trophy, smiled.

Ten cakes and two dozen cupcakes were prepared by the bakery.

Next Tuesday is my birthday.

Rule: Every complete sentence needs a verb showing an action or a state of being.

Fragments with an –ing Verb or Past Participle but No Helping Verb

How to recognize: If the verb ends in ‑ing (walking, studying, smiling) or ‑ed (created, prepared) but is not the main verb of the sentence, then a helping verb (was, were, had been, etc.) must appear nearby. If not, you have a fragment.

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

The children walking through the park.

The paintings created by the students.

Students studying every night for the SAT.

The actress smiling at the crowd.

Two Ways to Fix:

Method 1: Add a helping verb (to complete the verb phrase) or change the verb form.

The children were walking through the park.

The paintings were created by the students.

The students had been studying every night for the SAT.

The actress was smiling at the crowd.

OR

The actress smiled at the crowd.

Method 2: Use the –ing or –ed form as an adjective (a participle) and add a separate main verb.

The children walking through the park shouted with joy.

The paintings created by the students were hung in the hallway.

The students studying every night for the SAT were sleep-deprived.

The actress, smiling at the crowd, accepted the award.

Rule: An ‑ing or ‑ed word cannot function as the sentence’s only verb unless it has a helping verb or is part of a larger clause with another main verb.

Fragments Without a Subject

How to Recognize:

Ask yourself: “Who is doing the action?” If there is no answer, the sentence is missing a subject. Sometimes these fragments also overlap with the errors we’ve already discussed (e.g., an –ing verb without a subject).

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

After reading all the assigned material. (Who read it?)

Wanted to discuss her grades with the teacher. (Who wanted to?)

Contemplating the meaning of life. (Who was?)

Corrected Versions:

Phil went to bed after reading all the assigned material.

Amanda wanted to discuss her grades with the teacher.

She was contemplating the meaning of life.

Rule: Every complete sentence must have both a subject (the “who” or “what”) and a verb (what the subject is doing or being).

Fragments That Are Subordinate (Dependent) Clauses

A dependent (subordinate) clause has both a subject and a verb, but cannot stand alone as a complete sentence. This happens when the clause begins with a subordinating conjunction and is not attached to a main clause.

Common Subordinating Conjunctions:

after, although, as, as if, because, before, even though, ever since, if, in order that, just as, since, so that, though, unless, until, when, whenever, where, whether, whereas, whichever, while

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

While I was parking the car.

When he finished baking cupcakes.

Since she owns two horses.

Each one has both a subject and a verb (“I was parking,” “he finished,” “she owns”), but the subordinating word (while, when, since) makes the thought incomplete.

Corrected Versions (add an independent clause):

While I was parking the car, I saw a cat run across the driveway.

When he finished baking cupcakes, I iced them.

Since she owns two horses, she is going to give me riding lessons.

Rule: If a sentence begins with a subordinating conjunction, it must also include an independent clause to complete the thought.

Fragments Caused by Added Detail

Sometimes, a fragment occurs when extra detail is written as if it were a full sentence, but it doesn’t contain a complete thought on its own.

These often begin with phrases like: such as, including, for example.

If you see a “sentence” starting this way, always check: Does it have its own subject and verb? If not, it’s a fragment.

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

I enjoy seeing animals at the zoo. Such as monkeys, zebras, and lions.

Julia enjoys watching anime. For example, YuYu Hakusho and Princess Mononoke.

I like to eat sweets, such as: donuts, chocolate, and candy.

Ways to Fix:

(1) Attach the detail directly to the main sentence:

I enjoy seeing animals such as monkeys, zebras, and lions at the zoo.

(2) Add a subject and a verb to make the fragment a full sentence:

Julia enjoys watching anime. For example, she watches YuYu Hakusho and Princess Mononoke.

(3) If you use a colon, make sure the part before the colon is a complete sentence:

I like to eat sweets: donuts, chocolate, and candy.

OR: I like to eat sweets, such as donuts, chocolate, and candy.

Rule: Added detail words (such as, including, for example) must connect to a complete sentence, not stand alone.

Fragments with a Relative Clause, Appositive, or Prepositional Phrase

Relative clauses, appositives, and prepositional phrases are excellent for adding detail — but they cannot form sentences all by themselves.

How to Recognize: Try crossing out the extra detail (the clause/phrase in commas or beginning with a preposition). If nothing complete is left, the sentence is a fragment.

Wrong / Fragment Examples:

John, who won the trophy four years in a row. (No main verb)

In the newspapers. (No subject or verb)

The trophy, which was given to the person who could cook an omelette the fastest. (No main verb)

Santa Claus, the jolly man in the red suit. (No verb)

Corrected Versions:

John, who won the trophy four years in a row, congratulated his competitors.

→ John congratulated his competitors.

John’s victory was announced in the newspapers.

→ John’s victory was announced.

The trophy, which was given to the person who could cook an omelette the fastest, was shaped like an egg.

→ The trophy was shaped like an egg.

Santa Claus, the jolly man in the red suit, ate all my cookies.

→ Santa Claus ate all my cookies.

Rule: If you remove the nonessential words (relative clause, appositive, or prepositional phrase), the sentence must still be complete on its own.

Congratulations — now you’ve learned all six types of fragments and how to fix them!

Now that you know how to recognize and correct fragments, the next step is to look at the opposite problem: when sentences are incorrectly joined together. On the SAT and in formal writing, this mistake is known as a run-on sentence or a comma splice.

What is a Run-on?

A run-on sentence happens when two or more independent clauses (complete sentences) are joined together incorrectly.

A common misconception: A run-on is not simply “a long sentence.”

A sentence can be 200+ words long and still be grammatically correct.

What matters is how the clauses are joined.

There are three main types of run-ons:

Comma Splices

Fused Sentences

Incorrect Use of Conjunctive Adverbs

Comma Splices

A comma splice occurs when two complete sentences are connected by only a comma.

A comma alone can never connect two independent clauses.

It must be followed by a coordinating conjunction (FANBOYS) or replaced with stronger punctuation.

Wrong / Fragment Example:

She was offered the prestigious job, she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Why Wrong? Two independent clauses → just a comma in between.

Fused Sentences (a.k.a. “Run-ons with No Punctuation”)

A fused sentence occurs when two sentences are joined with no punctuation at all.

Look for two separate subjects and verbs “running into each other” without the correct joining word or punctuation.

Wrong Example:

She was offered the prestigious job she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Why Wrong? Two independent clauses, but nothing separates them.

Incorrectly Punctuated Conjunctive Adverbs

A conjunctive adverb (however, therefore, moreover, consequently, nevertheless, thus, etc.) cannot, by itself, join two sentences with just a comma.

Conjunctive adverbs require either:

a semicolon before them → ; however,

or a period before them → . However,

Wrong Example:

She was offered the prestigious job, however, she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Why Wrong? A comma surrounds “however,” but the two clauses on either side are complete sentences, making it a run-on.

Correcting Run-Ons

Here are the 6 main strategies to fix run-ons.

Separate into two sentences.

She was offered the prestigious job. She turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Use a comma + FANBOYS (For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So).

She was offered the prestigious job, but she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Use a semicolon.

She was offered the prestigious job; she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Use a semicolon + conjunctive adverb.

She was offered the prestigious job; however, she turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

Make one clause subordinate.

Since she did not want to move to Texas, she turned down the prestigious job that she was offered.

Omit the repeated subject (when both clauses have the same subject).

She was offered the prestigious job but turned it down because she did not want to move to Texas.

(No comma needed here because the subject “she” is not repeated after the conjunction.)

Strategies for Identifying and Fixing Fragments and Run-ons

Fragments and run-ons are tested most often in Improving Sentences questions, but they can also appear in Identifying Errors and Improving Paragraphs.

Follow these steps whenever you suspect a fragment or run-on:

Step 1: Find the Simple Sentence

Locate the subject and main verb.

If it’s hard to find, cross out any prepositional phrases, appositives, or non-essential (extra) clauses.

What remains should still be a grammatically complete sentence.

Step 2: Check for Common Fragment/Run-on “Danger Signs”

Look closely for these red flags:

-ing or -ed verbs: Do they have the right helping verb?

Clause with a subordinating conjunction (because, although, since, while, if, etc.): Is it attached to a main clause?

Added-detail openers (for example, such as, including): Do they stand alone without a subject/verb?

Conjunctive adverbs with only commas (however, moreover, therefore, consequently): Wrong — needs a period or semicolon before.

Semicolon + FANBOYS: Wrong — semicolon already acts as the connector.

A single comma in the middle of two sentences: Likely a comma splice.

Step 3: Immediately Rule Out Wrong Choices

Eliminate any answers that leave you with a fragment or run-on.

A strong elimination method saves time on SAT/standardized test writing.

Step 4: Watch Two Tricky Patterns

Non-essential clauses (beginning with “which, who, that”) → Must always be attached to a complete sentence.

My father, who is one of the greatest violinists in the world, and he plays piano as well. Fragment

My father, who is one of the greatest violinists in the world, plays piano as well. Correct

Comma splices (most common SAT trap) → Two sentences joined by only a comma. Must be fixed.

Step 5: Pick the Best Answer Choice

After eliminating fragments/run-ons, select the choice that:

Is complete and grammatically correct

Uses clear pronouns with defined antecedents

Avoids unnecessary words, articles, or prepositions

Uses concise and direct phrasing

Avoids overuse of gerunds (-ing forms)

Has no dangling or misplaced modifiers

Worked Example

Original sentence:

Santa Fe is one of the oldest cities in the United States, its adobe architecture, spectacular setting, and clear, radiant light have long made it a magnet for artists.

Step A: Identify the Error

A comma appears in the middle.

Can I split it into two sentences?

Santa Fe is one of the oldest cities in the United States. Its adobe architecture, spectacular setting, and clear, radiant light have long made it a magnet for artists. Correct.

Conclusion: This is a comma splice.

Step B: Evaluate Choices

(A) Santa Fe is one of the oldest cities in the United States, its… → Same as original, still a comma splice.

(B) Santa Fe, which is one of the oldest cities in the United States, its… → Non-essential clause + stray subject “its” = not a full sentence.

(C) Santa Fe, which is one of the oldest cities in the United States, has… → Check after removing the clause: Santa Fe has adobe architecture… have long made it a magnet. → mismatch / incomplete. Wrong.

(D) Santa Fe is one of the oldest cities in the United States; its… → Semicolon correctly joins two full sentences.

(E) Santa Fe, one of the oldest cities in the United States, and it… → After removing appositive: Santa Fe and it adobe architecture… → nonsense. Wrong.

Step C: Final Answer

Choice (D).

Santa Fe is one of the oldest cities in the United States; its adobe architecture, spectacular setting, and clear, radiant light have long made it a magnet for artists.

Key takeaway for students:

Always check the subject and verb.

Watch out for “danger signs” (comma splice, dangling clause, lone -ing, etc.).

Eliminate systematically.

Prefer concise, grammatically correct, fully independent sentences.

Related Posts

Struggling with the Digital SAT Reading & Writing section? Discover 5 common mistakes students make and actionable tips to boost your score!

Struggling with SAT Reading? Learn a proven 4-step method to tackle passages effectively, avoid traps, and improve your test score!